Review: 'Open, Heaven' by Séan Hewitt

Exploring queerness, obsession, and detachment, 'Open, Heaven' offers a stark meditation on longing—but at what cost?

At its core, Open, Heaven serves as an exploration of boyhood, with its many tensions and alienations. These are further complicated by the protagonist’s queerness, which emerges despite the barrenness of the landscape it springs from.

Guilt and shame have long been woven into queer narratives, shaped by a history of oppression, but here, they function less as an honest reckoning with internal conflict and more as a reinforcement of the idea that queerness is inseparable from suffering. The novel’s rural, small-town setting justifies their presence to some degree, but their stifling weight feels more like an inevitability than an inquiry.

And though Hewitt’s language has proven capable of sublime acrobatics in the past, here it moves at an even pace, devoid of its usual dynamism, intent only on reaching its destination. It halts often, circling back on itself, lingering over past ruminations, whether relevant or not. This, inevitably, disrupts its flow.

Similarly, the prose lays thoughts bare, emptied of ambiguity or allure, flattening every opportunity for sensory or intellectual engagement. The reader is kept firmly at a distance, unable to explore or interpret beyond what is dictated.

As though on a leash, they are led step by step through a story of uneasy obsession. But though it fronts as love, no true feeling takes hold in Open, Heaven.

Love, guilt, longing, dread—none find respite in the words or deeds of the protagonist, a self-proclaimed fantasist. And none extend to his ailing brother or parents, though all three spend the length of the novel constructing bridges from the breakable materials at their disposal.

Similarly, James' fixation on Luke, the slightly older boy who unsettles him, is driven more by projection than by any genuine connection. His intense focus on Luke’s physiology, including the warmth of his spittle, gives their dynamic a clinical, almost detached quality.

This detachment extends to James’ own body: the yeasty smells of his want are described with a blunt frankness that feels uncomfortably intimate, as though the rawness of his physicality lacks the softening lens of self-awareness.

But unlike the visceral, painful exploration of desire, friendship, and sexuality in Keith Hale’s Clicking Beat on the Brink of Nada, where emotions are presented as complex, disjointed, and deeply felt, James’ feelings for Luke exist more as untouchable archetypes. Despite the circular trajectory of his thoughts, they remain insubstantial, too distant to truly grasp or connect with.

The examination of the human psyche, with its many flaws and complexities, is deserving of nothing but praise. However, when judging a novel’s appeal, readability remains an unforgiving metric. Ultimately, the world of Open, Heaven feels too flat, and its quiet emotions too detached from existence, to offer a truly meaningful exploration.

An advance copy was provided by Knopf.

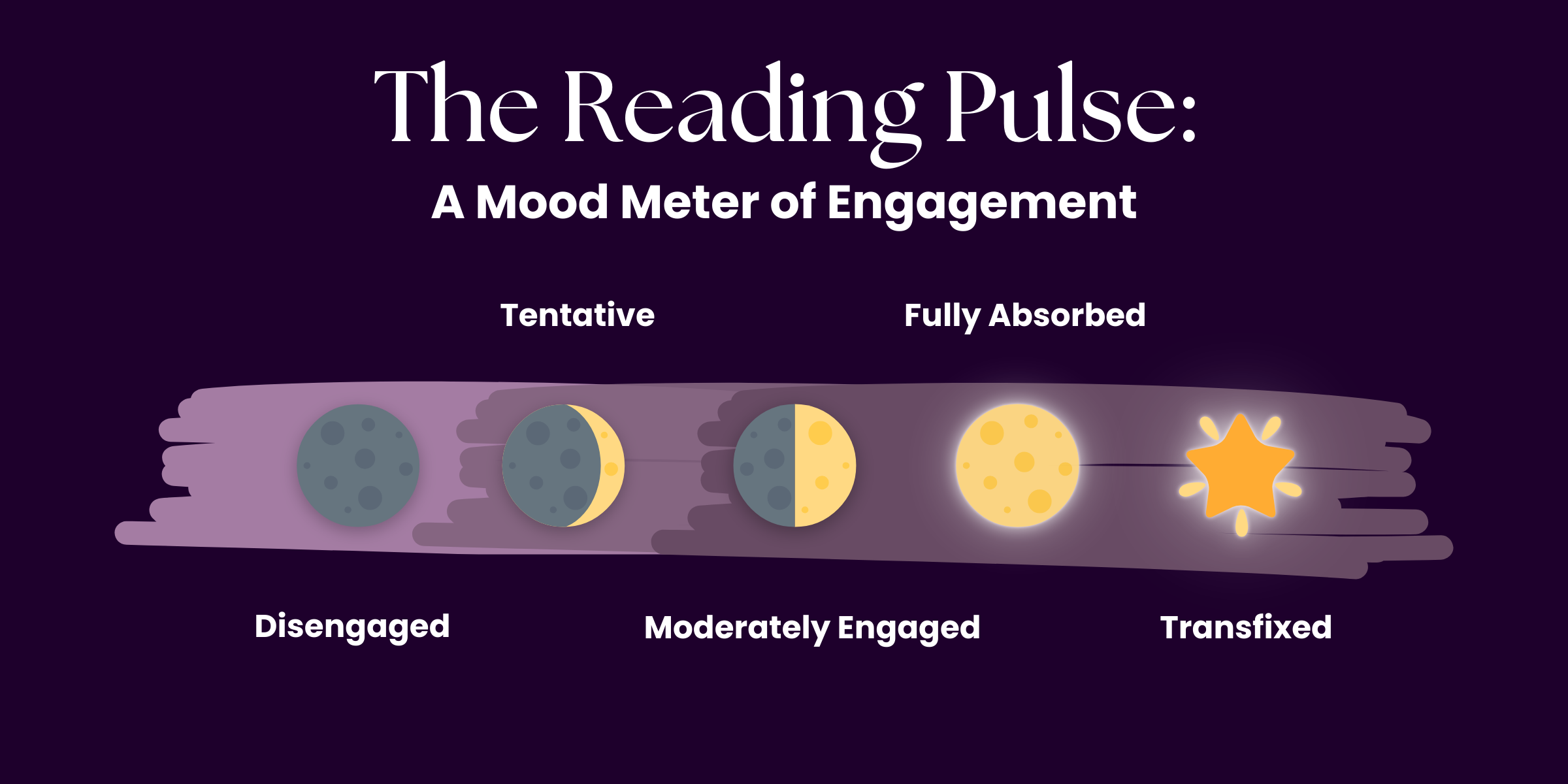

Mood Meter

🌑🌒🌑🌑🌒

Genres

LGBTQ+ Literary Fiction

Coming-of-Age Fiction

Publication Date

April 15, 2025