Corrupting the Neutral: Reimagining English Through Gender

How does language carve us into being?

Unlike many languages, English is remarkably "neutral," with no gendered articles, noun derivatives, or verb endings to mark the masculine, the feminine, or the neutral.

While it's true that English relies on gendered pronouns and certain occupational titles (e.g., "actress," "waitress," "businessman"), these features aren't as embedded in the structure of the language as they are in, say, French, Spanish, or Polish, which prevents English from feeling inherently gendered.

Its neutrality creates a subtle distance between language and identity — a quiet removal that leaves expression open, fluid, and unanchored.

As a result, English adapts to pronouns like the singular “they” with relative ease, allowing both language and everyday existence to feel more inclusive.

But what if this wasn’t the case?

What if English, like so many of its linguistic cousins, had carried gendered noun endings into its modern form? Would it sharpen distinctions we barely register today? Would it distort meaning, or deepen hidden biases?

In this experiment, we’ll attempt a gradual reimagining of English, starting with a single, deliberate mutation: gendered noun derivation, i.e., the creation of gendered forms for nouns.

1. Sculpting New Endings

Let’s start with a simple framework:

- -or (masculine noun)

- -ess (feminine noun)

- -ex (neutral/non-binary noun)

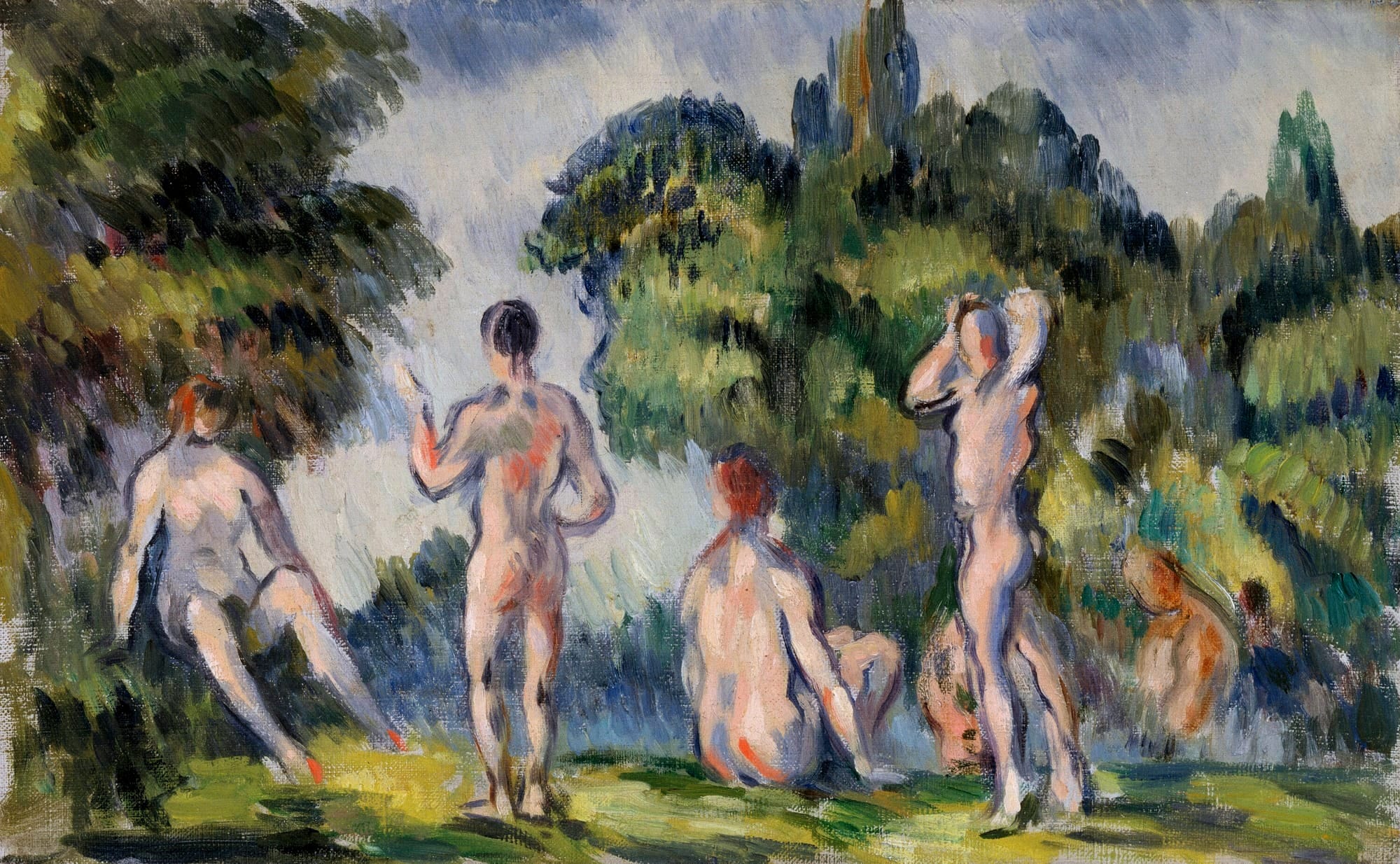

2. A Canvas of Distortion

Modern English

Reimagined English

“The artor painted a landscape.” (masculine)

“The artess painted a landscape.” (feminine)

“The artex painted a landscape.” (neutral)

3. Carving Perception

Modern English

Reimagined English

“The doctor spoke to the visitor.” (male doctor/male visitor)

“The doctor spoke to the visitess.” (male doctor/female visitor)

“The doctor spoke to the visitex.” (male doctor/neutral visitor)

“The doctess spoke to the visitor.” (female doctor/male visitor)

“The doctess spoke to the visitess.” (female doctor/female visitor)

“The doctess spoke to the visitex.” (female doctor/neutral visitor)

and so on…

Notice how gender now intrudes on perception. Even the act of fulfilling a certain role is immediately tied to gender. “Doctess” might be unconsciously perceived as less authoritative than “doctor,” depending on cultural biases.

Notice, too, how the default noun remains masculine. Shifting to a feminine or neutral form suddenly forces the underlying lexical mutation into view—the subtle reshaping of a word’s base structure that carries new layers of meaning, with all its quiet implications.

Think of how “actor” becomes “actress” in English, a slight shift that can carry assumptions about status, skill, and even pay. Now imagine that happening to every noun you use to refer to people, items, or abstract entities.

4. Forming Abstractions

Modern English

Reimagined English

"Hopor remains." (Hope imagined as masculine)

"Hopess remains." (Hope imagined as feminine)

"Hopex remains." (Hope as a neutral force)

Suddenly, even abstract ideas are chained to identity.

5. Tension in the Sculpture of Inclusion and Exclusion

Modern English

Reimagined English

"Welcome, travellors!" (male group)

"Welcome, travellesses!" (female group)

"Welcome, travellexes!" (mixed or neutral group)

Imagine such a sign on the doors of a hostel. No matter which option is chosen, someone will inevitably feel secondary, perhaps even invisible. In this way, gendered language forces constant decisions: Who is included? Who is erased?

6. Preliminary Sketches: Reflections on Gendered Language

Even though we're exploring gendered noun derivation, which is only the tip of the iceberg, we can already feel how sentences grow heavier, clumsier, burdened by the weight of their own subtext.

Assigning gender to everything, from professions to abstract concepts, sharpens social roles in stark, artificial ways, rooting gender norms deep within the architecture of language. And through subtle shifts in emotional tone, these small grammatical changes culminate in real-world power dynamics.

It's this rigidity, threaded through traditionally gendered languages, that leaves non-binary people without a grammatical "home," no space shaped for them within the system.

Neutral forms feel like afterthoughts or grammatical leftovers, with their clunky constructions marking them as "special cases," widening the rift between inclusive thinking and "the standard."

The deeper issue is this: gendered language automatically normalises binary thinking, embedding it in every sentence, every interaction, and making life that much more challenging to navigate for trans and non-binary people.

Simply put, language reveals its limits by making some identities "ungrammatical," introducing friction into everyday communication. You can no longer speak without categorising or reinforcing roles the world has long since outgrown.

7. Bonus: Painting with Gendered Adjectives

While letting gender reshape noun forms isn’t entirely foreign to English, adjective derivation remains a largely unexplored territory. And yet, this concept is central to how gender operates in many of the world’s languages, making it an area worth exploring, if only in part.

Changing the endings of words is akin to shape-shifting—an act already common in many languages, where expression morphs to reflect gender. But in English, most words remain untouched, including the ones that launch reality into being.

Introducing such mutations into adjectives wouldn’t just embellish language; it would fundamentally rewire the emotional and social signals they carry.

7.1. Recasting the Adjective

- -an (masculine adjective)

- -ine (feminine adjective)

- -un (neutral adjective)

7.2. In the Shadow of the Example: Defining the Frame

Modern English

Reimagined English

strongan (masculine)

strongine (feminine)

strongun (neutral)

7.3. Bringing the Sentence to Life

Modern English

Reimagined English

"The bravan artor painted a brightan muror." (masculine)

"The bravine artess painted a brightine muress." (feminine)

"The bravun artex painted a brightun murex." (neutral)

Of course, these examples don't account for gendered verb conjugation or the way different words can carry different genders within a single sentence. For clarity’s sake, we're keeping the concept as uncomplicated as possible.

To really grasp the implications of gendered adjective use, we need to turn to a scenario where exclusion becomes almost inevitable: marketing slogans.

7.4. The Chisel of Language: Carving Identity into Slogans

Modern English

Reimagined English

"You are strongan. You are bravan. You were made to lead." (masculine)

"You are strongine. You are bravine. You were made to lead." (feminine)

"You are strongun. You are bravun. You were made to lead." (neutral)

Here, the choice of adjective form becomes a strategic decision, as even slogans naturally fracture along gendered lines. Who, then, gets to "own" bravery, strength, and authenticity?

On a structural level, language—even when intended to unify or inspire—fragments people into categories.

In this framework, the gender linked to traditional authority serves as the linguistic default, while those on the margins are relegated to the periphery, both in the discourse on conceptual change and in everyday communication, including public narratives.

Thus, we begin to see how identity is not only reflected but actively imposed on every effort, every entity, every emotion. In this light, how can we view progress as anything other than a fundamental need for linguistic restructuring?